Book Boards

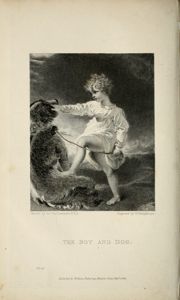

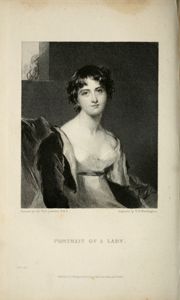

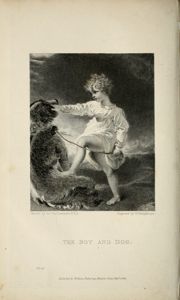

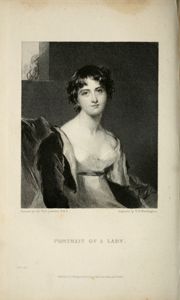

Frontispiece

painted by Sir Thomas Lawrence, engraved by W. Humphreys

Title Page

The Bijou;

or Annual of Literature and the Arts

compiled by William

Fraser

London: William Pickering,

1828

Dedication Page

| [Page v] |

|

The few observations which are necessary to be prefixed to this volume, will contain

little more than acknowledgements to the distinguished literary characters, and

eminent artists whose respective productions adorn its pages; as it is on those

productions the Publisher rests his hopes that it will be deemed entitled to an

elevated station among the Annual publications, not of this country only, but of

Europe. Far from wishing, however, to institute invidious comparisons, he only

assets for it an equal claim to the notice and patronage of the public; for whether

with respect to its graphic illustrations, or its literary merits, he feels assured

that it will not be found inferior to any, even if it does not excel most, of its

contemporaries.

To describe the Editor's obligations to this various friends in adequate terms would

require space infinitely beyond that to which a preface is necessarily limited; but

in briefly expressing his gratitude to the celebrated characters who have cheerfully

afforded him the assistance of their talents, he will not only perform a grateful

duty, but at the same time tacitly urge the pretensions which he considers "THE

BIJOU" to possess to public favor.

To sir Walter Scott the proprietors and himself

| [Page vi] |

|

are

indebted for the interesting letter explanatory of the picture of his family, with

an

engraving of which, through the liberality of its possessor Sir Adam Ferguson, and

the painter Mr. Wilkie, they have been able to enrich the Work. Nor is it too much

to expect that if every other recommendation were wanting, that plate, and still more

the description by which it is accompanied would prove irresistable attractions to

the world; for who can be indifferent to so pleasing a memorial of a writer to whose

merits England, Europe, nay, the whole civilized world, has offered its homage and

its praise. Conspicuous as that letter is among the literary beauties of these

sheets,—and to it may be attributed an interest as unfading as the reputation of its

writer—almost all the popular authors of the day have contributed one or more

scintillations of their genius; and it is with feelings of pride, admiration, and

gratitude, that the Editor and Proprietors offer their warmest acknowledgements to

John Gibson Lockhart, Esq.,1 Mrs. Hemans, Sir Egerton Brydges, Bart.; Sir Thomas

Elmsley Croft, Bart.; the Rev. Blanco White; Barry Cornwall; L. E. L.; Miss Mitford;

Mrs. Pickersgill;

| [Page vii] |

|

Miss Roberts; the writer of the

“Diary of an Ennuyée;” R. P. Gillies, Esq.;2 J. Montgomery, Esq.; the Rev.

W. Lisle Bowles; the author of “The Subaltern;” Delta; Horace Smith, Esq.; Charles

Lamb, Esq.; the Ettrick Shepherd; Allan Cunningham, Esq.; N. T. Carrington,Esq

[sic]; and to the other contributors.

In expressing the Editor's thanks in a separate paragraph to S. T. Coleridge, Esq.'

It must not be supposed that his obligations are the less important to those whose

names have just been mentioned; but where a favor has been conferred in a peculiar

manner, it at least demands that it should be peculiarly acknowledged. Mr.

Coleridge, in the most liberal manner, permitted the Editor to select what he pleased

from all his unpublished MSS., and it will be seen from the “Wanderings of Cain,”

though unfinished, and the other pieces bearing that Gentleman's name, that whenever

he may favour the world with a perfect collection of his writings he will adduce new

and powerful claims upon its respect.

In another, but no less important department of talent, the Proprietors have yet to

pay their debt of gratitude. From the invaluable favours he has conferred upon the

work, the first among those claimants is he, who is the first in professional

reputation, in liberality, and in all which characterises a Gentle-

| [Page viii] |

|

man, Sir Thomas Lawrence, the President of the Royal Academy,

who has bestowed on it three of his unrivalled productions; and which, it is needless

to say, are of themselves sufficient to place "THE BIJOU" in the foremost rank of

the

embellished publications of Europe.

To H. W. Pickersgill, Esq. R. A. the Proprietors are deeply indebted for the

gratuitous use of his beautiful picture “The Oriental Love-Letter,” in the Council

Room of the Royal Academy; and which derives considerable interest from the elegant

illustration by which it is accompanied from the pen of his accomplished wife. To

Mr. W. H. Worthington the Proprietors are grateful for the loan of his painting "The

Suitors Rejected."

In consequence of a resemblance between the principal incident in the Tale of

HALLORAN THE PEDLAR and the catastrophe described in a recent publication of deserved

popularity, both evidently referring to the same historical fact, it is necessary,

in

order to prevent the suspicion of plagiarism, to state that the Tale of Halloran was

written, and in the hands of the publisher, long previously to the appearance of the

Novel where a similar circumstance is related. Many most valuable papers, nearly

sufficient to form another volume, remain in the Editor's possession; for the obvious

reason of superabundance of matter, it was impossible to insert them in the present

work.

| [Page ix] |

|

Amidst other literary curiosities, two will be found which derive their chief

attraction from the illustrious rank and eminent virtues of their authors: these

are, a translation of the celebrated Epistle of Servius Sulpicius to M. T. Cicero,

by

his present Majesty; and of Cicero's Epistle to Servius Sulpicius, by the lamented

Duke of York, both written as exercises at a very early age.

The selection of Graphic Illustrations was made by Mr. Robert Balmanno, Secretary

of

the Artists' Fund, and the Publisher.

Whether THE BIJOU be worthy of its name, and how far the proprietors have redeemed

the claim pledged in their prospectus, must be left to the public to determine. It

has been their unceasing endeavour to concentrate specimens of the varied talent,

both in literature and art, for which this country is renowned; to allow the powers

of the pencil, and the connotations of the mind, mutually to relieve and and adorn

each other, where

| "Each lends to each a double charm, |

| Like pearls upon an Ethiop's arm;" |

And as no trouble has been considered too laborious, no expense too great to

accomplish this object, they submit the result of their exertions with confidence

unalloyed by presumption, but not unmixed with hope.

W. F.

| [Page [xi]] |

|

| [Page xii] |

|

xii LIST OF EMBELLISHMENTS.

_______

| [Page [xiii]] |

|

PAGE

- The Child and Flowers. By Mrs. Hemans

........................ 1

- Ballad from the Norman French. By J.G. Lockhart, Esq... 4

- Sonnets. By Sir Egerton Brydges, Bart.

......................... 11

- The City of the Dead. By L. E. L.

..................................13

- Night and Death. By the Rev. Joseph Blanco White

........16

- The Wanderings of Cain. By S. T. Coleridge, Esq. .........

17

- Verses for an Album. By Charles Lamb, Esq.

................ 24

- Lines written in the Vale of Zoar

..................................... 25

- An aged Widow's own Words By James Hogg, the

Ettrick

Shepherd.................................................... 26

- From the Italian

.............................................................. 27

- Work without Hope. By S. T. Coleridge, Esq.

............... 28

- The Poet-Warrior. By Allan Cunningham

....................... 29

- The Rose. By Sir Thomas E. Croft, Bart.

....................... 31

- To my Child. By B. C.

.................................................. 32

- Letter from Sir Walter Scott, Bart.

................................. 33

- The Night before the Battle of Montiel. From the

Spanish of Don Juan Algalaba ............................... 39

- Jessy of Kibe's Farm. By Miss M. R. Mitford

............... 65

- Song. By T. K. Hervey, Esq.

........................................ 76

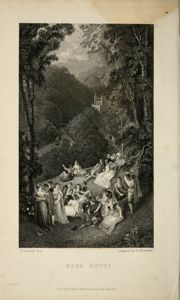

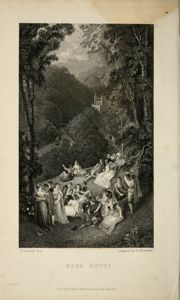

- Sans Souci. By. L. E. L.

............................................... 77

- A Lament for the Decline of Chivalry. By T. Hood,

Esq. Author of "Whims and Oddities" .................... 75

- The Purple Evening. By the author of 'Stray Leaves'

...... 80

- Scotland. By Robert Southey, Esq. Poet Laureat ..........

81

- To a Friend. By Lady Caroline Lambe

.......................... 89

- On his Majesty's Return to Windsor Castle. By the

Rev. W. Lisle Bowles ............................................ 91

- The Hellweathers. By N. T. Carrington, Esq. Author

of "Dartmoor" ....................................................... 92

- Imitation from the Persian. By Dr. Southey

................... 98

- The Suitors Rejected. By Miss Emma Roberts, Author

of "Memoirs of the Houses of York and Lancaster." 99

- Ane Waefu' Scots Pastoral. By James Hogg, the

Ettrick Shepherd ................................................. 108

| [Page xiv] |

|

CONTENTS.

PAGE

- Anacreontic. By T. K. Hervey,

Esq............................... 112

- The Ritter Von Reichenstein

......................................... 114

- A familiar Epistle to Sir Thomas Lawrence. By Barry

Cornwall .............................................................. 139

- Youth and Age. By S. T. Coleridge,

Esq........................144

- A Day Dream. By S. T. Coleridge,

Esq........................ .146

- Marie's Grave. By the Author of "The

Subaltern"............148

- The National Norwegian Song. By W. H. Leeds,

Esq.....173

- An Address to the Lost Wig of John Bell, Esq. By a

Tyro......................................................................176

- A Simile, on a Lady's Portrait. By James Montgo-

mery, Esq..............................................................181

- The Epistle of Servius Sulpicius to Marcus Tullius

Cicero. Translated by his Majesty..........................183

- The Epistle of Marcus Tullius Cicero to Servius Sul-

picius. Translated by his late Royal Highness

the Duke of York

..................................................188

- The Lover's Invocation. By Miss

Mitford....................... 191

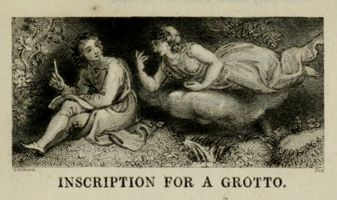

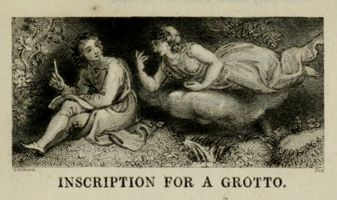

- Inscription for a Grotto. By Horace Smith,

Esq...............193

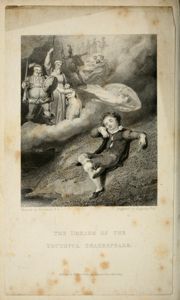

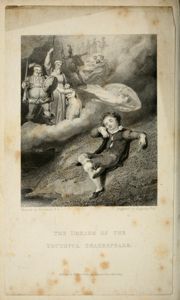

- The Infant

Shakespeare..................................................195

- On a Little Girl. By W.

Fraser........................................ 198

- Canzonet. By John Bird,

Esq..........................................200

- The Two Founts. By S. T. Coleridge,

Esq.......................202

- Halloran the Pedlar. By the writer of the "Diary

of

an Ennuyée" ......................................................205

- Morning. By D. L. Richardson,

Esq................................240

- The Oriental Love-Letter. By Mrs. Pickersgill,

Author

of the "Tales of the Harem"

....................................241

- Mount Carmel. By H. Neele,

Esq.................................. 234

- Sketch from Life

............................................................242

- Beau Leverton

...............................................................261

- Essex and the Maid of Honour. By Horace Smith, Esq...

285

- Humble Love. By William

Fraser....................................312

- Haddon Hall. By H.

B....................................................315

- My [sic.] Native Land. By Delta, of Blackwood's

Magazine....319

- [Index of Embellishments]

- [Index of Authors]

- [Notes]

| [Page 1] |

|

| All good and guiltless thou art. |

| Some transient griefs will touch thy heart, |

| Griefs that along thy altered face |

| Will breathe a more subduing grace, |

| Than even those looks of joy that lie |

| On the soft cheek of infancy. |

| WILSON, To a Sleeping Child |

| HAST thou been in the woods with the honey-bee? |

1 |

| Hast thou been with the lamb in the pastures free? |

2 |

| With the hare through to copses and the dingles wild? |

3 |

| With the butterfly over the heath, fair child? |

4 |

| Yes: the light fall of thy bounding feet |

5 |

| Hath not startled the wren from her mossy seat; |

6 |

| Yet hast thou ranged the green forest-dells, |

7 |

| And brought back a treasure of buds and bells. |

8 |

| Thou know'st not the sweetness, by antique song |

9 |

| Breathed o'er the names of that flowery throng; |

10 |

| The woodbine, the primrose, the violet dim, |

11 |

| The lily that gleams by the fountain's brim: |

12 |

| [Page 2] |

|

| These are old words, that have made each grove |

13 |

| A dreary haunt for romance and love; |

14 |

| Each sunny bank, where faint odours lie |

15 |

| A place for the gushings of Poesy. |

16 |

| Thou know'st not the light wherewith fairy lore |

17 |

| Sprinkles the turf and the daisies o'er; |

18 |

| Enough for thee are the dews that sleep |

19 |

| Like hidden gems in the flower-urns deep; |

20 |

| Enough the rich crimson spots that dwell |

21 |

| Midst the gold of the cowslip's perfumed cell; |

22 |

| And the by the blossoming sweet-briars shed, |

23 |

| And the beauty that bows the wood-hyacinth's head. |

24 |

| Oh! Happy child in thy fawn-like glee! |

25 |

| What is remembrance or thought to thee? |

26 |

| Fill thy bright locks with those gifts of spring, |

27 |

| O'er thy green pathway their colours fling; |

28 |

| Bind them in chaplet and wild festoon— |

29 |

| What if to droop and to perish soon? |

30 |

| Nature hath mines of such wealth—and thou |

31 |

| Never wilt prize its delights as now! |

32 |

| For a day is coming to quell the tone |

33 |

| That rings in thy laughter, thou joyous one! |

34 |

| And to dim thy brow with a touch of care. |

35 |

| Under the gloss of its clustering hair; |

36 |

| [Page 3] |

|

| And to tame the flash of thy cloudless eyes |

37 |

| Into the stillness of autumn skies; |

38 |

| And to teach thee that grief hath her needful part, |

39 |

| Midst the hidden things of each human heart! |

40 |

| Yet shall we mourn, gentle child! for this? |

41 |

| Life hath enough of yet holier bliss! |

42 |

| Such be thy portion!—the bliss to look |

43 |

| With a reverent spirit, through nature's book; |

44 |

| By fount, by forest, by river's line, |

45 |

| To track the paths of a love divine; |

46 |

| To read its deep meanings—to see and hear |

47 |

| God in earth's garden—and not to fear. |

48 |

| [Page 4] |

|

Ballad from the Norman French

| Here beginneth a song which made in the Wood of Bel-Regard by a Good

Companion,

|

| who put himself there to eschew the horrible Creature of Justices

Trail-Baston.

|

| IN rhyme I clothe derision, my fancy takes thereto |

1 |

| So scorn I this provision, provided here of new; |

2 |

| The thing whereof my geste I frame I wish 'twere yet to do, |

3 |

| An guard not God and Holy Dame, 'tis war that must ensue. |

4 |

| I mean the articles abhorred of this their Trail-baston; |

5 |

| Except the king himself our lord, God send his malison |

6 |

| On the devisers of the same: cursed be they everyone, |

7 |

| For full they be of sinful blame, and reason have they none. |

8 |

| [Page 5] |

|

| Sir, if my boy offended me now, and I my hand but lift |

9 |

| To teach him by a cuff or two what's governance and thrift: |

10 |

| This rascal vile his bill doth file, attaches me of wrong; |

11 |

| Forsooth, find bail, or lie in gaol, and rot the rogues among. |

12 |

| 'Tis forty pennies that they ask, a ransom fine for me; |

13 |

| And twenty more ('tis but a score) for my Lord Sheriff's fee: |

14 |

| Else of his deepest dungeon the darkness I must dree; |

15 |

| Is this of justice, masters?— Behold my case and see. |

16 |

| Away, then, to the greenwood! to the pleasant shade away! |

17 |

| There evil none of law doth wonne, nor harmful perjury. |

18 |

| I'll to the wood of Bel-regard, where freely flies the jay, |

19 |

| And without fail the nightingale is chaunting of her lay. |

20 |

| But for that cursed dozen,God [sic] shew them small pitie! |

21 |

| Among their lying voices, they have indicted me |

22 |

| Of wicked thefts and robberies and other felonie, |

23 |

| That I dare no more, as heretofore, among my friends to be. |

24 |

| [Page 6] |

|

| In peace and war my service my lord the king hath ta'en, |

25 |

| In Flanders, and in Scotland, and in Gascoyne his domain; |

26 |

| But now I'll never, while I wis, be mounted man again, |

27 |

| To pleasure such a man as this I've spent much time in vain. |

28 |

| But if these cursed jurors do not amend them so |

29 |

| That I to my own country may freely ride and go, |

30 |

| The head that I can come at shall jump when I've my blow; |

31 |

| Their menacings, and all such things, them to the winds I

throw. |

32 |

| The Martin and the Neville are worthy folk indeed; |

33 |

| Their prayers are sure, albeit we're poor— salvation be their

meed! |

34 |

| But for Belflour and Spigurnel, they are a cruel seed; |

35 |

| God send them in my keeping— ha! They should not soon be freed! |

36 |

| I'd teach them well this noble game of Trail-baston to know; |

37 |

| On every chine I'd stamp the same, and every nape also; |

38 |

| [Page 7] |

|

| O'er every inch in all their frame I'd make my cudgel go; |

39 |

| To lop their tongues I'd think no shame, nor yet their lips to

sew. |

40 |

| The man that did begin it first, without redemption |

41 |

| He is for evermore accurst— he never can atone: |

42 |

| Great sin is his, I tell ye true, for many an honest man |

43 |

| For fear hath joined the outlaw's crew, since these new laws

began. |

44 |

| There's many a wildwood thief this hour was peaceful man

whil'ere, |

45 |

| The fear of prison hath such power even guiltless breast to

scare: |

46 |

| 'Tis this which maketh many a one to sleep beneath the tree; |

47 |

| And he that these new laws begun, the curse of God take he! |

48 |

| Ye merchants and ye wandering freres, ye may well curse with

me, |

49 |

| For ye are painful travellers, while laws like this shall be; |

50 |

| The king's broad letter in your hand but little can bestead, |

51 |

| For he perforce must bid men stand, that hath nor home nor

bread. |

52 |

| [Page 8] |

|

| All ye who are indicted! I pray you come to me |

53 |

| To the greenwood, the pleasant wood, where's niether suit nor

plea, |

54 |

| But only the wild creatures and many a spreading tree |

55 |

| For there's little in common law but doubt and misery. |

56 |

| If at your need you've skill to read, you're summon'd ne'er the

less |

57 |

| To shew your lore the Bench before, and great is your redress; |

58 |

| Clerk the most clerkly though you be, expect the same penance: |

59 |

| 'Tis true a Bishop turns the key: God grant deliverance. |

60 |

| In honesty I speak—for me, I'd rather sleep beneath |

61 |

| The canopy of the green tree, yea, on the naked heath, |

62 |

| Than lie even in a Bishop's vault for many a weary day; |

63 |

| And he that 'twixt such choice would halt, he is a fool I say. |

64 |

| I had a name that none could blame, but that is lost and gone, |

65 |

| For lawyer-tricks have made me mix with people that have none. |

66 |

| [Page 9] |

|

| I dare not shew my face no mo among my friends and kin: |

67 |

| The poor man now is sold I trow, whate'er the rich, may win. |

68 |

| To risk I cannot fancy much, what, lost, is ne'er repaid |

69 |

| To put my life within their clutch in truth I'm sore afraid; |

70 |

| This is no question about gold that might be won again, |

71 |

| If once they had me in their hold 'tis death they'd make my

pain. |

72 |

| Some one perchance my friend will be, such hope not yet I lack; |

73 |

| The men that speak this ill of me, they speak behind my back; |

74 |

| I know it would their hearts delight, if they my blood could

spill, |

75 |

| But God, in all the devil's spite, can save me if he will. |

76 |

| There's one can save me life and limb, the blessed Mary's

child, |

77 |

| And I can broadly pray to him; my soul is undefiled: |

78 |

| The innocent he'll not despise, by envious tongues undone. |

79 |

| God curse the smiling enemies that I have leaned upon! |

80 |

| [Page 10] |

|

| If meeting a companion I shew my archerie, |

81 |

| My neighbour will be saying, "He's of some companie, |

82 |

| He goes to cage him in the wood, and worke his old foleye," |

83 |

| Thus men do hunt me like the boar, and life's no life for me. |

84 |

| But if I seem more cunning about the law than they, |

85 |

| "Ha! ha! Some old conspirator well trained in tricks," they'll

say; |

86 |

| O wheresoe'er doth ride the Eyre, I must keep well away:— |

87 |

| Such neighbourhood I hold not good; shame fall on such I pray. |

88 |

| I pray you, all good people, to say for me a prayer, |

89 |

| That I in peace may once again to mine own land repair: |

90 |

| I never was a homicide—not within my will—I swear, |

91 |

| Nor robber, christian folk to spoil, that on their way did

fare. |

92 |

| This rhyme was made within the wood, beneath a broad bay tree; |

93 |

| There singeth merle and nightingale, and falcon hovers free: |

94 |

| I wrote this skin, because within was much more sore memory, |

95 |

| And here I lay it by the way—that found my rhyme may be. |

96 |

| [Page 11] |

|

By Sir Egerton Brydges,

Bart

| I. |

1 |

| WHEN dead is all the vigour of the frame, |

2 |

| And the dull heart beats languid, notes of praise |

3 |

| May issue the desponding sprite to raise: |

4 |

| But weekly strikes the voice of slow-sent fame; |

5 |

| Empty we deem the echo of a name: |

6 |

| Inward we turn; we list no fairy lays; |

7 |

| Nor seek on golden palaces to gaze; |

8 |

| Nor wreaths from groups of smiling fair to claim! |

9 |

| Thus strange is fate:— we meet the hollow cheer, |

10 |

| When struck by age the cold insensate ear |

11 |

| No more with trembling extasy can hear, |

12 |

| But yet one thought a lasting a joy can give |

13 |

| That we, as not for self alone we live, |

14 |

| To others bore the boon, we would from them receive! |

15 |

| [Page 12] |

|

| II. |

16 |

| TEXTURE of the mightiest splendor, force and art, |

17 |

| Wove in the fine loom of the subtlest brain, |

18 |

| The brilliance of thy colours shines in vain, |

19 |

| If steeped not in the fountains of the heart! |

20 |

| If those pure waves no added strength impart, |

21 |

| If thence the web no new attraction gain, |

22 |

| Sure is the test, no genuine muse would deign |

23 |

| Her inspiration on the work to dart! |

24 |

| High intellect, magnific though thou be, |

25 |

| Yet if thou hast not power to raise the glow |

26 |

| Of grand and deep emotions, which to thee |

27 |

| Backward its own o'ershadowing hues may throw; |

28 |

| Vapid thy fruits are; barren is thy ray; |

29 |

| And worthless shall thy splendour die away! |

30 |

| [Page 13] |

|

| 'Twas dark with cypresses and yews which cast |

1 |

| Drear shadows on the fairer trees and flowers— |

2 |

| Affections latest signs. * * * |

3 |

| Dark portal of another world— the grave— |

4 |

| I do not fear thy shadow; and methinks, |

5 |

| If I may make my own heart oracle,— |

6 |

| The many long to enter thee, for thou |

7 |

| Alone canst reunite the loved and lost |

8 |

| With those who pine for them. I fear thee not; |

9 |

| I only fear mine own unworthiness, |

10 |

| Lest it prove barrier to my hope, and make |

11 |

| Another parting in another world. |

12 |

| ************************************************************************* |

13 |

| 1. |

14 |

| LAUREL! Oh fling thy green boughs on air, |

15 |

| There is dew on thy branches, what doth it do there? |

16 |

| Thou art worn on the conquerors shield, |

17 |

| When his country receives him from glory's red field; |

18 |

| Thou that art wreathed round the lyre of the bard, |

19 |

| When the song of its sweetness has won its reward. |

20 |

| Earth's changeless and sacred— thou proud laurel tree! |

21 |

| The ears of the midnight, why hang they on thee? |

22 |

| [Page 14] |

|

| 2. |

23 |

| Rose of the morning, the blushing and bright, |

24 |

| Thou whose whole life is noe breath of delight; |

25 |

| Beloved of the maiden, the chosen to bind |

26 |

| Her dark tresses' wealth from the wild summer wind. |

27 |

| Fair tablet, still vowed to the thoughts of the lover, |

28 |

| Whose rich leaves with sweet secrets are written all over; |

29 |

| Fragrant as blooming— thou lovely rose tree! |

30 |

| The tears of the midnight, why hang they on thee? |

31 |

| 3. |

32 |

| Dark cypress I see thee— thou art my reply, |

33 |

| Why the tears of the night on thy comrade trees lie; |

34 |

| That laurel it wreathed the red brow of the brave, |

35 |

| Yet thy shadow lies black on the warriors grave. |

36 |

| That rose was less bright than the lip which it prest, |

37 |

| Yet thy sad branches sweep o'er the maiden's last rest: |

38 |

| The brave and the lovely alike they are sleeping, |

39 |

| I marvel no more rose and laurel are weeping. |

40 |

| 4. |

41 |

| Yet sunbeam of heaven thou fall'st on the tomb— |

42 |

| Why pausest thou by such dwelling of doom? |

43 |

| Before thee the grove and the garden are spread; |

44 |

| Why lingerest thou round the place of the dead? |

45 |

| [Page 15] |

|

| Thou art from another, a lovelier sphere, |

46 |

| Unknown to the sorrows that darken us here. |

47 |

| Thou art as a herald of hope from above:— |

48 |

| Weep mourner no more o'er thy grief and thy love; |

49 |

| Still thy heart in its beating, be glad of such rest, |

50 |

| Though it call from thy bosom its dearest and best. |

51 |

| Weep no more that affection thus loosens its tie, |

52 |

| Weep no more the the loved and the loving must die |

53 |

| Weep no more o'er the cold dust that lies at your feet, |

54 |

| But gaze on yon starry world— there ye shall meet. |

55 |

| 5. |

56 |

| O heart of mine! Is there not One dwelling there |

57 |

| To whom thy love clings in its hope and its prayer? |

58 |

| For whose sake thou numberest each hour of the day, |

59 |

| As a link in the fetters that keep me away; |

60 |

| When I think of the glad and the beautiful home, |

61 |

| Which oft in my dreams to my spirit hath come; |

62 |

| That when our last sleep on my eyelids hath prest; |

63 |

| That I may be with thee at home and at rest: |

64 |

| When wanderer no longer on life's weary shore, |

65 |

| I may kneel at thy feet, and part from thee no more; |

66 |

| While death holds such hope forth to soothe and to save, |

67 |

| Oh sumbeam of heaven thou mayest will light the grave. |

68 |

| [Page 16] |

|

By the Rev. Joseph

Blanco White

Dedicated to S.T. Coleridge, Esq. By his sincere friend, Joseph

Blanco White.

| MYSTERIOUS night, when the first man but knew |

1 |

| Thee by report, unseen, and heard they name, |

2 |

| Did he not tremble for this lovely frame, |

3 |

| This glorious canopy of light and blue? |

4 |

| Yet 'neath a curtain of translucent dew |

5 |

| Bathed in the rays of the great setting flame, |

6 |

| Hesperus, with the host of heaven, came, |

7 |

| And lo! creation widened on his view! |

8 |

| Who could have thought what darkness lay concealed |

9 |

| Within thy beams, oh Sun? Or who could find, |

10 |

| Whil'st fly, and leaf, and insect stood revealed, |

11 |

| That to such endless orbs thou mad'st us blind? |

12 |

| Weak man! Why to shun death, this anxious strife? |

13 |

| If light can thus deceive, wherefore not

life? |

14 |

| [Page 17] |

|

The Wanderings of Cain: A Fragment.

"A LITTLE further, O my father, yet a little farther, and we shall come into the open

moonlight!" Their road was through a forest of fir- trees; at its entrance the trees

stood at distances from each other, and the path was broad, and the moonlight, and

the moonlight shadows reposed upon it, and appeared quietly to inhabit that solitude.

But soon the path winded and became narrow; the sun at high noon sometimes speckled,

but never illumined it, and now it was dark as a cavern.

"It is dark, O my father!" said Enos, "but the path under our feet is mooth and soft,

and we shall soon come out into the open moonlight. Ah, why dost thou groan so

deeply?"

"Lead on my child," said Cain, "guide me, little child." And the innocent little

child clasped a finger of the hand which had murdered the righteous Abel, and he

guided his father. "The fir branches drip upon thee my son." — "Yea, pleasantly,

father, for I ran fast and eagerly to bring thee the pitcher and the

| [Page 18] |

|

cake, and my body is not yet cool. How happy the squirrels are

that feed on these fir trees! they leap from bough to bough, and the old squirrels

play round their young ones in the nest. I clomb a tree yesterday at noon, O my

father, that I might play with them, but they leapt away from the branches, even to

the slender twigs did they leap, and in amoment I beheld them on antoher tree. Why,

O

my fahter, would they not play with me? Is it because we are not so happy as they?

Is

it because I groan sometimes even as thou groanest?" Then Cain stopped and stifling

his groans, he sank to the earth, and the child Enos stood in the darkness beside

him; and Cain lifted up his voice, and cried bitterly, and said, "The Mighty One that

persecuteth me is on this side and on that; he pursueth my soul like the wind, like

the sand- blast he passeth through me; he is around me even as the air, O that I

might be utterly no more! I desire to die — yea, the things that never had life,

neither move they upon the earth — behold they seem precious to mine eyes. O that

a

man might live without the breath of his nostrils, so I might abide in darkness and

blackness, and an empty space! Yea, I would lie down, I would not rise, neither would

I stir my limbs till I became as the rock in the den of the lion, on which the young

lion resteth his head whilst he sleepeth. For the torrent that roareth far off hath

a

voice; and the clouds in heaven look terribly on me; the mighty one who is against

me

speaketh in

| [Page 19] |

|

the wind of the cedar grove; and in silence

I am dried up." Then Enos spake to his father, "Arise my father, arise, we are but

a

little way from the place where I found the cake and the pitcher;" and Cain said,

"How knowest thou?" and the child answered — "Behold, the bare rocks are a few of

they strides distant from the forest; and while even now thou wert lifting up thy

voice, I heard the echo." Then the child took hold of his father, as if he would

raise him, and Cain being faint and feeble rose slowly on his knees and pressed

himself against the trunk of a fir, and stood upright and followed the child. The

path was dark till within three strides' length of its termination when it turned

suddenly; the thick black trees formed a low arch, and the moonlight appeared for

a

moment like a dazzling portal. Enos ran before and stood in the open air; and when

Cain, his father, emerged from the darkness the child was affrighted, for the mighty

limbs of Cain were wasted as by fire; his hair was black, and matted into loathly

curls, and his countenance was dark and wild, and told in a strange and terrible

language of agonies that had been, and were, and were still to continue to be.

The scene around was desolate; as far as the eye could reach, it was desolate; the

bare rocks faced each other, and left a long and wide interval of their white sand.

You might wander on and look round and round, and peep into the crevices of the

rocks, and discover nothing that acknowledged the in-

| [Page 20] |

|

fluence of the seasons. There was no spring, no summer, no autumn, and the winter's

snow that would have been lovely, fell not on these hot rocks and scorching sands.

Never morning lark had poised himself over this desert; but the huge serpent often

hissed there beneath the talons of the vulture, and the vulture screamed, his wings

imprisoned within the coilds of the serpent. The pointed and shattered summits of

the

ridges of the rocks made a rude mimicry of human concerns, and seemed to prophecy

mutely of things that then were not; steeples, and battlements, and ships with naked

masts. As far from the wood as a boy might sling a pebble of the brook, there was

one

rock by itself at a small distance from the main ridge. It had been precipitated

there perhaps by the terrible groan the earth gave when our first father fell. Before

you approached, it appeared to lie flat on the ground, but its base slanted from its

point, and between its points and the sands a tall man might stand upright. It was

here that Enos had found the pitcher and cake, and to this place he led his father.

But ere they arrived there they beheld a human shape; his back was towards them, and

they were coming up unperceived when they heard him smite his breast and cry aloud,

"Wo, is me! wo, is me! I must never die again, and yet I am perishing with thirst

and

hunger."

The face of Cain turned pale; but Enos said, "Ere yet I could speak, I am sure, O

my

father, that

| [Page 21] |

|

I heard that voice. Have not I often said

that I remembered a sweet voice. O my father! this is it;" and Cain trembled

exceedingly. The voice was sweet indeed, but it was thin and querulous like that of

a

feeble slave in misery, who despairs altogether, yet can not refrain himself from

weeping and lamentation. Enos crept softly round the base of the rock, and stood

before the stranger, and looked up into his face. And the Shape shrieked, and turned

round, and Cain beheld him, that his limbs and his face were those of his brother

Abel whom he had killed; and Cain stood like one who struggles in his sleep because

of the exceeding terribleness of a dream; and ere he had recovered himself from the

tumult of his agitation, the Shape fell at this feet, and embraced his knees, and

cried out with a bitter outcry, "Thou eldest born of Adam, whom Eve, my mother,

brought forth, cease to torment me! I was feeding my flocks in green pastures by the

side of quiet rivers, and thou killedst me; and now I am in misery." Then Cain closed

his eyes, and hid them with his hands — and again he opened his eyes, and looked

around him, and said to Enos "What beholdest thou? Didst thou hear a voice, my son?"

"Yes, my father, I beheld a man in unclean garments, and he uttered a sweet voice,

full of lamentation." Then Cain raised up the shape that was like Abel, and said,

"The creator of our father, who had

| [Page 22] |

|

respect unto thee,

and unto thy offering, wherefore hath he forsaken thee?" Then the Shape shrieked a

second time, and rent his garment, and his naked skin was like the white sands

beneath their feet; and he shrieked yet a third time, and threw himself on his face

upon the sand that was black with the shadow of the rock, and Cain and Enos sate

beside him; the child by his right hand, and Cain by his left. They were all three

under the rock, and within the shadow. The Shape that was like Abel raised himself

up, and spake to the child; "I know where the cold , waters are, but I may not drink,

wherefore didst thou then take away my pitcher?" but Cain said, "Didst thou not find

favour in the sight of the Lord thy god?" The Shape answered, "The Lord is God of

the

living only, the dead have another god." Then the child Enos lifted up his eyes and

prayed; but Cain rejoiced secretly in his heart. "Wretched shall they be all the days

of their mortal life," exclaimed the Shape, "who sacrifice worthy and acceptable

sacrifices to the God of the dead; but after death their toil ceaseth. Woe is me,

for

I was well beloved by the God of the living, and cruel wert thou, O my brother, who

didst snatch me away from his power and his dominion." Having uttered these words,

he

rose suddenly, and fled over the sands, and Cain said in his heart, "The curse of

the

lords is on me — but who is the God of the dead?" and he ran after the shape, and

the

Shape fled

| [Page 23] |

|

shrieking over the sands, and the sands rose

like white mists behind the steps of Cain, but the feet of him that was not like Abel

disturbed not the sands. He greatly outrun Cain, and turning short, he wheeled round,

and came again to the rock where they had been sitting, and where Enos still stood;

and the child caught hold of his garment as he passed by, and that theman had fallen

upon the ground; and Cain stopped, and beholding him not, said, "he has passed into

the dark woods," and walked slowly back to the rocks, and when he reached it the

child told him that he had caught hold of his garment as he passed by, and that the

man had fallen upon the ground; and Cain once more sat beside him, and said — "Abel,

my brother, I would lament for thee, but that the spirit within me is withered, and

burnt up with extreme agony. Now, I pray thee, by thy flocks and by thy pastures,

and

by the quiet rivers which thou lovest, that thou tell me all that thou knowest. Who

is the God of the dead? where doth he make his dwelling? what sacrifices are

acceptable unto him? for I have offered, but have not been received; I have prayed,

and have not been heard; and how can I be afflicted more than I already am?" The

Shape arose and answered — "O that thou hadst had pity on me as I will have pity on

thee. Follow me, son of Adam! and bring thy child with thee:" and they three passed

over the white sands between the rocks, silent as their shadows.

| [Page 24] |

|

| FRESH clad from heaven in robes of white, |

1 |

| A young probationer of light, |

2 |

| Thou wert, my soul, an Album bright. |

3 |

| A spotless leaf; but thought, and care — |

4 |

| And friends and foes, in foul or fair, |

5 |

| Have "written strange defeature" there. |

6 |

| And time, with heaviest hand of all, |

7 |

| Like that fierce writing on the wall, |

8 |

| Hath stamp'd sad dates — he can't recall. |

9 |

| And error, gilding worst designs — |

10 |

| Like speckled snake that strays and shines — |

11 |

| Betrays his path by crooked lines. |

12 |

| And vice hath left his ugly blot — |

13 |

| And good resolves, a moment hot, |

14 |

| Fairly began — but finished not. |

15 |

| A fruitless late remorse doth trace — |

16 |

| Like Hebrew lore, a backward pace — |

17 |

| Her irrecoverable race. |

18 |

| [Page 25] |

|

| Disjointed numbers — sense unknit — |

19 |

| Huge reams of folly — shreds of wit — |

20 |

| Compose the mingled mass of it. |

21 |

| My scalded eyes no longer brook, |

22 |

| Upon this ink- blurr'd thing to look. |

23 |

| Go — shut the leaves — and clasp the book! — |

24 |

Lines Written in the Vale of Zoar, Coast of Arabia

| A SCENE of Araby! — but not the blest; — |

1 |

| Behold a multitude of mountains wild |

2 |

| And bare and cloudless to the skies up- piled |

3 |

| In forky peaks, and shapes uncouth, possest |

4 |

| Of grandeur stern indeed, but beauty none; |

5 |

| Their sterile sides, by herb, or blade undrest, |

6 |

| Burning and whitening in the ardent sun. |

7 |

| Amid the crags — her undisputed reign — |

8 |

| Pale Desolation sits, and sadly smiles, |

9 |

| And half the horror of her state beguiles, |

10 |

| To see her empire spreading to the plain; |

11 |

| For there even wandering Arabs seldom stray, |

12 |

| Or, coming, do but eye the drear domain, |

13 |

| And haste, as from the vale of Death, away! |

14 |

| [Page 26] |

|

An Aged Widow's Own Words

By James Hogg, the

Ettrick Shepherd

| O IS he gane my good auld man? |

1 |

| And am I left forlorn? |

2 |

| And is that manly heart at rest,, |

3 |

| The kindest e'ver was born? |

4 |

| We've sojourned here through hope and fear |

5 |

| For fifty years and three, |

6 |

| And ne'er in all that happy time, |

7 |

| Said he harsh word to me. |

8 |

| And mony a braw and boardly son |

9 |

| And daughters in their prime, |

10 |

| His tremling hand laid in the grave; |

11 |

| Lang, lang afore the time. |

12 |

| I dinna greet the day to see |

13 |

| That he to them has gane, |

14 |

| But O 'tis feafu' thus to be |

15 |

| Left in a world alane. |

16 |

| [Page 27] |

|

| Wi' a poor worn and broken heart, |

17 |

| Whose race of joy is run,. |

18 |

| And scarce has little opening left, |

19 |

| For aught aneath the sun. |

20 |

| My life nor death I winna crave, |

21 |

| Nor fret for yet despond, |

22 |

| But a' my hope is in the grave |

23 |

| And the dear hame beyond. |

24 |

| MY LILLA gave me yester morn |

1 |

| A rose methinks in Eden born, |

2 |

| And as she gave it, little elf, |

3 |

| Blushed like another rose herself |

4 |

| Then said I, full of tenderness, |

5 |

| "Since this sweet rose I owe to you, |

6 |

| "Dear girl, why may I not possess |

7 |

| "The lovelier rose that gave it too?" |

8 |

| [Page 28] |

|

Work Without Hope. Lines Composed on a Day in February

| ALL Nature seems at work. Slugs leave their lair — |

1 |

| The bees are stirring — birds are on the wing — |

2 |

| And WINTER slumbering in the open air, |

3 |

| Wears on his smiling face a dream of Spring! |

4 |

| And I, the while, the sole unbusy thing, |

5 |

| Nor honey make, nor pair, nor build, nor sing. |

6 |

| Yet well I ken the banks where Amaranths blow, |

7 |

| Have traced the forest whence streams of nectar flow. |

8 |

| Bloom, O ye Amaranths! Bloom for whom ye may — |

9 |

| For me ye bloom not! Glide, rich streams, away! |

10 |

| With lips unbrightened, wreathless brow, I stroll: |

11 |

| And would you learn the spells that drowse my soul? |

12 |

| WORK WITHOUT HOPE draws nectar in a sieve, |

13 |

| And HOPE without an OBJECT cannot live. |

14 |

| [Page 29] |

|

| 1. |

1 |

| STAYED is the war- horse in his strength, |

2 |

| Broke is the barbed arrow, |

3 |

| The spell has conquered on Nithside, |

4 |

| Which won of yore on Yarrow. |

5 |

| O did he bear a charmed sword |

6 |

| That for no mail would tarry, |

7 |

| And on his youthful head a helm |

8 |

| Was forged in land of fairy. |

9 |

| Did Saxon shaft and war axe dint |

10 |

| Fall on charm's mail and elfin flint? |

11 |

| 2. |

12 |

| His spell was valour, and he came |

13 |

| When warrior's hearts were coldest, |

14 |

| And poured his fire through peasant's souls, |

15 |

| And led and ruled the boldest. |

16 |

| He with flushed brow, and flashing eyes, |

17 |

| And right arm bare and gory, |

18 |

| [Page 30] |

|

| Rushed reeking o'er the lives of men, |

19 |

| And turned our shame to glory. |

20 |

| A hero's soul was his, and higher |

21 |

| The minstrel's love, and poet's fire. |

22 |

| 3. |

23 |

| Seek for a dark and down cast eye, |

24 |

| A glance 'mongst men the mildest, |

25 |

| Seek for a bearing haught and high |

26 |

| Can daunt and awe the wildest. |

27 |

| Seek one whose soul is tenderness |

28 |

| Is steeped — who to the lyre |

29 |

| Can pour out song as fast and bright |

30 |

| As heaven can pour its fire. |

31 |

| Seek him, and when thou find'st him, kneel, |

32 |

| Though thou hadst gold spurs on thy heel. |

33 |

| [Page 31] |

|

By Sir

Thomas E. Croft, Bart.

| La rose que ta main chérie |

1 |

| Hier a sauvé de la mort, |

2 |

| Est aujourd'hui pâle et flétrie; — |

3 |

| Tel est des fleurs le triste sort. |

4 |

| Reconnaissante de ta peine, |

5 |

| En mourant cette aimable fleur, |

6 |

| Légue a tes joues sa rougeur, |

7 |

| Son doux parfum à ton haleine. |

8 |

| The rose, alas! Thy guardian hand |

9 |

| Sav'd yesterday from dying, |

10 |

| Pale, wan, and wither'd from its stem, |

11 |

| Is now in ruins lying: |

12 |

| But the fond flower, to shew she still |

13 |

| Was grateful, e'en in death, |

14 |

| Her blushes to thy cheek bequeathed, |

15 |

| Her perfume to thy breath. |

16 |

| [Page 32] |

|

By B.C. [pseud. for Bryan

Walker Procter]

| CHILD of my heart! My sweet, belov'd first-bórn! |

1 |

| Thou dove, who tidings bring'st of calmer hours! |

2 |

| Thou rainbow, who dost come when all the showers |

3 |

| Are past, — or passing! Rose which hath no thorn, — |

4 |

| No pain, no blemish, — pure and unforlorn, |

5 |

| Untouched — untainted — O, my flower of flowers! |

6 |

| More welcome than to bees are summer bowers, — |

7 |

| To seamen stranded life-assuring morn. |

8 |

| Welcome! a thousand welcomes! Care, who clings |

9 |

| Round all, seems loosening now her snake-like fold! |

10 |

| New hope springs upwards, and the bright world seems |

11 |

| Cast back into her youth of endless springs! — |

12 |

| — Sweet mother, is it so? — or grow I old, |

13 |

| Bewildered in divine Elysian dreams? |

14 |

Figure 2: Sir Walter Scott and Family

painted by David Wilkie, Esq., engraved by W. H.

Worthington

| [Page 33] |

|

Letter from Sir Walter Scott, Bart.

By Sir Walter Scott,

Bart.

LETTER FROM SIR WALTER SCOTT TO SIR ADAM FERGUSON, DESCRIPTIVE OF A PICTURE PAINTED

AT ABBOTSFORD BY DAVID WILKIE, ESQ. R. A., AND EXHIBITED AT THE ROYAL ACADEMY IN

1818.

MY DEAR ADAM — The picture you mention has something in it of rather a domestic

character, as the personages are represented in a sort of masquerade, such being the

pleasure of the accomplished painter. Nevertheless, if you, the proprietor, incline

to have it engraved, I do not see that I am entitled to make any objection.

But Mr. * * * mentions besides, a desire to have anecdotes of my private and domestic

life, or, as he expresses himslef, a portrait of the author in his nightgown and

slippers; — and this form you, who, I dare say, could furnish some anecdotes of our

younger days which might now seem ludicrous enough. Even as to my night gown and

slippers, I believe the time has been when the articles of my wardrobe were as

familiar to your memory as Poins's

| [Page 34] |

|

to Prince Henry, but

that period has been for some years past, and I cannot think it would be interesting

to the public to learn that I had changed my old robe-de-chambre for a handsome

douillette, when I was last at Paris.

The truth is, that a man of ordinary sense cannot be supposed delighted with the

species of gossip which, in the dearth of other news, recurs to such a quiet

individual as myself; and though, like a well-behaved lion of twenty years standing,

I am not inclined to vex myself about what I cannot help, I will not, in any case

in

which I can prevent it, be acessary to these follies. There is no man known at all

in

literature who may not have more to tell of his private life than I have: I have

surmounted no difficulties either of birth or education, nor have I been favored by

any particular advantages, and my life has been as void of incidents of importance,

as that of the "weary knife-grinder."

"Story! God bless you! I have none to tell, Sir."

The follies of youth ought long since to have passed away; and if the prejudices and

absurdities of age have come in their place, I will keep them, as Beau Tibbs did his

prospect, for the amusement of my domestic friends. A mere enumeration of the persons

in the sketch is all which I can possible permit to be published respecting myself

and my

| [Page 35] |

|

family; and, as must be the lot of humanity when

we look back seven or eight years, even what follows cannot be drawn up without some

very painful recollections.

The idea which our inimitable Wilkie adopted ws to represent our family group in the

garb of south-country peasants, supposed to be concerting a merry-making, for which

some of the preparations are seen. The place is the terrace near Kayside, commanding

an extensive view toward the Eildon-hills. 1. The sitting figure, in the dress of

a

miller, I believe, represents Sir Walter Scott, author of a few scores of volumes,

and proprietor of Abbotsford, in the County of Roxburgh. 2. In front, and presenting,

we may suppose, a country wag somewhat addicted to poaching, stands sir Adam

Ferguson, Knight, Keeper of the Regalia of Scotland. 3. In the background is a very

handsome old man, upwards of eighty-four years old at the time, painted in his own

character of a shepherd. He also belonged to numerous clan of Scott. He used to claim

credit for three things unusual among the southland shepherds: first, that he had

never been fou in the course of his life; secondly, that he never had struck a man

in

anger; thirdly, that though entrusted with the the management of large sales of

stock, he had never lost a penny for his master by a bad debt. He died soon aterwards

at Abbotsford. 4, 5, 6. Of the three female figures

| [Page 36] |

|

the

elder is the late regretted mother of the family represented. 5. The young person

most forward in the group is Miss Sophia Charlotte Scott, now Mrs. John Gibson

Lockhart; and 6, her younger sister, Miss ann Scott. Both are represented as

ewe-milkers, with their leglins, or milk-pails. 7. On the left hand of the shepherd,

the young man holding a fowling-piece is the eldest son of Sir Walter, now Captain

in

King's Hussars. 8. The boy is the youngest of the family, Charles Scott, now of

Brazen Nose College, Oxford. The two dogs were distinguished favorites of the family;

the large one was a stag-hound of the old Highland breed, called Maida, and one of

the hansomest dogs that could be found; it was a present to me from the chief of

Glengary, and was highly valued, both on account of his beauty, his fidelity, and

the

great rarity of the breed. The other is little Highland terrier, called

Ourisk (goblin), of a particualr kind, bred in Kintail. It was a

present from the honorable Mrs. Stuart Mackenzie, and is a valuable specimen of race

which is now also scarce. Maida, like Bran, Lerath, and other dogs of distinction,

slumbers "beneath his stone," distinguished by an epitaph, which to the honour of

Scottish scholarship be it spoken, has only one false quantity in two lines.

| Maidae marmorea dormis sub imagine Maida |

| Ad januam domini sit tibi terra levis. |

| [Page 37] |

|

Ourisk still survives, but like some other personages in the picture, with talents

and temper rather the worse for wear. She has become what Dr. Rutty, the Quaker,

records himself in his journal as having sometimes been — sinfully dogged and

snappish.

If it should suit Mr. * * *'s purpose to adopt the above illustrations, he is

heartily welcome to them, but I make it my especial bargain that nothing more is said

upon such a meagre subject.

It strikes me, however, that there is a story about old Thomas Scott, the shepherd,

which is characteristic, and which I will make your friend welcome to. Tom was, both

as a trusted servant, and as a rich fellow in his line, a person of considerable

importance among his class in the neighbourhood, and used to stickle a good deal to

keep his place in public opinion. Now, he suffered, in his own idea at least, from

the consequence assumed by a country neighbour, who, though neither so well reputed

for wealth or sagacity as Thomas Scott, had yet an advantage over him, from having

seen the late King, and used to take precedence upon all occasions when they chanced

to meet. Thomas suffered under this superiority. But after this sketch was finished,

and exhibited in London, the newspapers made it known that his present majesty had

condescended to take some notice of it. Delighted with the circumstance, Thomas Scott

set out on a most oppressively hot day, to walk five miles to Bowden,

| [Page 38] |

|

where his rival resided. He had no sooner entered the cottage

when he called out in his broad forest dialect — "Andro', man, did ye anes sey (see)

the King?" "In troth did I, Tam," answered Andro'; "sit down, and I'll tell ye a'

about it: — ye sey I was at Lonon, in a place they ca' the park, that is, no like

a

hained hog-fence, or like the four-nooked parks in this country — " "Hout awa," said

Thomas, "I have heard a' that before: I only came ower the know now to tell you,

that, if you have seen the king, the king has seen mey" (me). And so he returned with

a jocund heart, assuring his friends "it had done him muckle gude to settle accounts

with Andro'."

Jocere haec — as the old Laird of Restalrig writes to the Earl of Gowrie — farewell

my old, tried, and dear friend of forty long years. Our enjoyments must now be of

a

character less vivid than those we have shared together,

But still at our lot it were vain to repine, Youth cannot return, or the days of Lang

Syne.

Your's Affectionately,

Walter Scott.Abbotsford, 2d August, 1827.

| [Page 39] |

|

The Night before the Battle of Montiel: , A Dramatic Sketch

From the Spanish of

Don Juan Algalaba

[The battle of Montiel was that which determined the fate of Pedro the Cruel. Just

ten years before it took place he and Edward the Black Prince had utterly defeated

at Nejara Henry (called of Transtamara) Pedro's natural brother, the competitor

for the throne of Castile: But in the interval Pedro's cruelties had alienated the

affection of his subjects, and the murder of his wife Blanche of Bourbon, sister

to the King of France, had stirred up an enemy whom, being deserted by the English

Prince, he had no longer any sufficient means to resist.

Pedro's famous mistress, Maria de Padilla, was in the castle of Montiel when the

battle was fought, and after her lover was slain received the body and was

permitted to bury it.

The French army was commanded by the illustrous Bertrand du Guesclin — in whose

memoirs the highly picturesque details of the conflict, the subsequent meeting of

the brothers, and the death of Pedro, may be found. Le Begue was the French knight

who stabbed Pedro.]

SCENE — The Camp of Henry.

ALAIN DE LA HOUSSAYE AND LE BEGUE.

HOUSSAYE.

| I do remember even on such a sky |

1 |

| Kind Pedro's banner flaunted, even so calm |

2 |

| And heavy hung yon selfsame royal blazon |

3 |

| Upon the air, as the slow sun went down |

4 |

| The night before Nejara. |

5 |

| [Page 40] |

|

LE BEGUE.

| ‘Twas in Paris, |

6 |

| I heard the tidings of that filed; — I knew not |

7 |

| That my old friend rode in Prince Henry's host |

8 |

| Else had I not rejoiced. |

9 |

HOUSSAYE.

LE BEGUE.

| Yes, Alain — — |

11 |

| I had heard many things against Don Pedro, |

12 |

| Yet, truth to speak, it seemed to me foul scorn, |

13 |

| That one whose mother never had been married, |

14 |

| Should put his hand forth — clutching at the crown. |

15 |

HOUSSAYE.

| I hope we'll have no thoughts like these to-morrow. |

16 |

LE BEGUE.

| Not I, the fleurdelys will be i'the van. |

17 |

HOUSSAYE.

| My thoughts shall be upon the Lady Blanche. |

18 |

LE BEGUE.

| Aye, well they may — |

19 |

| That bloody Jewess — is it known if she |

20 |

| Be still with Pedro? Follows she the camp? |

21 |

HOUSSAYE.

| They say she doth — but see! Lord Onis comes, |

22 |

| And he can tell us further. |

23 |

LE BEGUE.

| The old lord |

24 |

| Walks very solemnly methinks to-night, |

25 |

| His pace is sober as a hooded priest. |

26 |

HOUSSAYE.

| Aye, and I'll warrant ye his thoughts more sober, |

27 |

| Than oft lie hid beneath the gown and cowl. |

28 |

LE BEGUE.

| [Page 41] |

|

| The chance is equal! be we French or Spaniard — |

30 |

| But if the day go darkly, and Don Henry |

31 |

| Find on Montiel the fortune of Nejara, — |

32 |

| No ransom for a traitor. |

33 |

HOUSSAYE.

| Look upon him! |

34 |

| There sits no selfish fear on Onis' brow; |

35 |

| He is a Spaniard, and we war in Spain. |

36 |

| The rival chiefs are brothers — and the swords |

37 |

| That glow even now in many a strenuous hand |

38 |

| As they receive the polish and the point, |

39 |

| Must gleam ere long before the eyes of kindred. |

40 |

| Where'er may fall the chance of victory, |

41 |

| Yon stream, amidst to-morrow's noontide brightness, |

42 |

| Will be more purple with Castilian blood, |

43 |

| Than now the broad sun sinking paints its face. |

44 |

LE BEGUE.

| He passes on — he takes no note of us. |

45 |

HOUSSAYE.

| We greet you well, Lord Onis! |

46 |

ONIS.

| Ha! fair Sirs! |

47 |

| I crave your pardon. Whither be ye bound? |

48 |

HOUSSAYE.

| Du Guesclin's trumpet hath not sounded yet? |

49 |

ONIS.

| They are together in the royal tent. |

50 |

| Anon we shall be summoned. |

51 |

LE BEGUE.

| Doth the prince, |

52 |

| (I crave your grace, the king) doth he to-morrow |

53 |

| Charge on the centre of his brother's battle? |

54 |

ONIS.

| I would it were not so; but, if I know him, |

55 |

| It would be heavy tiding for his ear, |

56 |

| [Page 42] |

|

| That any sword but his had found its sheath |

57 |

| Within the breast of Pedro. |

58 |

HOUSSAYE.

| Don Pedro's cuirass hath turned swords ere now — |

59 |

| And wielded by as ready hands as Henry's. |

60 |

ONIS.

| You speak the truth, Sir Alain de la Houssaye, |

61 |

LE BEGUE.

| You look for stubborn work, my Lord of Onis. |

62 |

ONIS.

| Sir Alain Houssaye has seen Pedro's plume |

63 |

| Rising and falling like a falcon's wing, |

64 |

| As far i'the front as e'er Plantagenet |

65 |

| Shewed his black crest. |

66 |

LE BEGUE.

| And yet the old adage |

67 |

| Hangs cruelty and cowardice together. |

68 |

ONIS.

| The man that coined the phrase had known no Pedro. |

69 |

| The old ancestral sense of dignity |

70 |

| Exalts our excellence if we be good, |

71 |

| And even if we be vicious, that high pride |

72 |

| Is not more inborn than inalienable; |

73 |

| At least ‘tis so with Pedro. ‘Twas the same |

74 |

| When Pedro stood no higher than his hilt, |

75 |

| A most imperious boy. God he defies, |

76 |

| And man he never feared. |

77 |

LE HOUSSAYE.

| This nobleness |

78 |

| Of kingly nature props e'en now a cause |

79 |

| That, had he been in aught a vulgar villain |

80 |

| [Page 43] |

|

| Had been as bare of man's aid as of God's; — |

81 |

| But hark! The trumpet. |

82 |

LE BEGUE.

[Exeunt Houssaye and Le Begue.

ONIS.

| Beautiful Valley! What a golden light |

84 |

| Is on thy bosom. Ha! the bells are ringing |

85 |

| In the church towers along yon green hill side |

86 |

| The vesper chaunt! Alas! What dreary knells |

87 |

| Must shake, next sunset, their gray pinnacles! |

88 |

[Exit.

The Tent of Henry of Transtamara.

HENRY — DU GUESCLIN — BISHOP PEREZ — ONIS — HOUSSAYE — LE BEGUE.

HENRY.

| Sit, gentlemen. Onis, we waited for thee. |

1 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| There is no need we should be long together; |

2 |

| We may do better service in our quarters: |

3 |

| My humble mind it was, most certainly, |

4 |

| That you, sir king, should take the right to-morrow, |

5 |

| Where, if our scouts bring true intelligence, |

6 |

| Don Pedro plants his Moors —- |

7 |

HENRY.

| Noble Du Guesclin, |

8 |

| We fight on Spanish ground, and I have here |

9 |

| Three thousand true men of Castile and Leon |

10 |

| Who serve me as their king — the which I am |

11 |

| [Page 44] |

|

| By the free choice of nobility |

12 |

| In open Cortes, aiding right of blood, |

13 |

| My brother having forfeited all title |

14 |

| By bloody acts of murder and oppression |

15 |

| Not to be counted — some of them ye know — |

16 |

| The which dissolved all claim to our allegiance, |

17 |

| And left us free (I mean the Lords of Spain) |

18 |

| To choose another wearer for the crown |

19 |

| Of old Pelayo; — of Pelayo's line |

20 |

| Am I, and justly now I wear that crown, |

21 |

| Though once there was a baton on my shield, |

22 |

| That stain being erased and nullified |

23 |

| By the decree I spake of —- Now their hearts |

24 |

| Would scarcely brook to see the post of honour |

25 |

| Filled by a stranger, howsoever noble |

26 |

| In blood, and whatsoever pennon rearing, |

27 |

| When I their king am present. Other reasons |

28 |

| I have already to your private ear |

29 |

| Sufficiently expounded. Is there need |

30 |

| That I recount them also? |

31 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| Since his highness |

32 |

| Is so resolved in this, my Lord of Onis, |

33 |

| I yield the matter — for myself I speak: |

34 |

| What says La Houssaye? |

35 |

HOUSSAYE.

| May it please the king, |

36 |

| Although your courtesy, noble Du Guesclin, |

37 |

| Hath brought me to the council, I am here |

38 |

| Not to oppose my voice to voice of yours — |

39 |

| [Page 45] |

|

| But having learned your pleasure and my part, |

40 |

| To tender, if need be, humble suggestion |

41 |

| Touching what falls to me — and crave your guidance — |

42 |

| Ride we then on the right? |

43 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| You and Le Begue, |

44 |

| Be there with Burgundy and Picardy, |

45 |

| Ye'll have the Moors to deal withal. Myself |

46 |

| Will set my light-limbed Bretons on the left; |

47 |

| Perchance, while that King Henry from our centre |

48 |

| Bears with his Spaniards on the bridge, the old ford |

49 |

| May serve our need as well. I think ‘tis certain, |

50 |

| Don Pedro, with his own Castilian spears, |

51 |

| Will bide your highness' onset—Spain to Spain! |

52 |

HENRY.

BISHOP.

| Now God protect King Henry! |

54 |

| The Lord of Hosts will battle for the right. |

55 |

LE BEGUE.

| We all shall do our best, my good Lord Bishop. |

56 |

ONIS.

[Aside to La Houssaye.]

| 'Twere vain you see for anyone to fight |

57 |

| Against the king's determination. |

58 |

HOUSSAYE.

| ‘Tis a most wild one! Heaven defend the issue. |

59 |

HENRY.

| What says La Houssaye? |

60 |

LE BEGUE.

| He prays heaven, my lord, |

61 |

| To send fair issue of to-morrow's field. |

62 |

| [Page 46] |

|

HENRY.

| 'Tis well; and now brave gentlemen of France |

63 |

| Good e'en be with you all. Let the dawn find us |

64 |

| Each at his post. |

65 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| My word shall be—QUEEN BLANCHE! |

66 |

HENRY.

DU GUESCLIN.

| They'll do well together. |

68 |

[The lords rise from their seats; a Trumpet is heard.

HENRY.

| What means this trumpet? thrice, too? |

69 |

[Enter a Castilian Herald in his tabard, attended by Officers

&c.

HERALD.

| By my mouth |

70 |

| Thus to King Sancho's baseborn son, Don Henry |

71 |

| Of Transtamara, speaks his rightful liege |

72 |

| The King, Don Pedro of Castille. Bold bastard, |

73 |

| That darest, not remembering the black curse |

74 |

| Which lies upon the memory of Count Julian, |

75 |

| To ape his ancient treason, and become |

76 |

| The guide of foreign spears into the heart |

77 |

| Of the fair Spanish land — I, born thy prince, |

78 |

| The lawful son and heir of thy dead father, |

79 |

| Whose erring love begot thee of a slave, |

80 |

| Bearded by thee within mine heritage, |

81 |

| Thee and the Bourbon's vassals whom thou guidest, |

82 |

| I full of scorn and wrath, as well I may be, |

83 |

| Have pity on all of those their fair allegiance |

84 |

| [Page 47] |

|

| Due to the Majesty of France hath led |

85 |

| Thus far within my realm — albeit their swords |

86 |

| Are girded on their thighs to serve the cause |

87 |

| Of my most sinful rebel; nor against |

88 |

| Even those, my own born liegemen, whom thy cunning |

89 |

| Hath led astray, so that forgetting oath |

90 |

| And fealty and solemn plight of homage, |

91 |

| They stand with thee against their sovereign's banner, |

92 |

| Am I entirely steeled. Therefore, in presence |

93 |

| Of brave Du Guesclin and his captains and |

94 |

| The Spaniards that are with them, I make offer |

95 |

| Of truce from this time till to-morrow's sunset, |

96 |

| Within which space — at the cool dawn ‘twere best — |

97 |

| Let lists be set upon the open field |

98 |

| Between these camps; and let the Lord Du Guesclin, |

99 |

| Upon the part of Henry Transtamara, |

100 |

| And the most noble Castro upon mine, |

101 |

| Be umpires of the day — and man to man, |

102 |

| And horse to horse — with lance, sword, mace, and knife — |

103 |

| Let two, whose hostile banners bear one sign, |

104 |

| Appeal to the unseen eye of God for judgment |

105 |

| On their conflicting titles; let the winner |

106 |

| Be undisputed king; unfearing love |

107 |

| Rest between him, whoever he may be, |

108 |

| [Page 48] |

|

| And all that are this day encamped here, |

109 |

| Moor, Frenchman, Spaniard; and let him who loses |

110 |

| Have death or exile; so shall knightly blood |

111 |

| Keep knightly veins, and wives' and mothers' eyes |

112 |

| On either side the rugged Pyrenees |

113 |

| Retain their tears unwept; so France in honour, |

114 |

| And Spain in peace, sweep from all memory |

115 |

| The traces of this tumult. I, the king, |

116 |

| Speak so: — Don Henry, called of Transtamara, |

117 |

[Flings down his gauntlet.

| Liftest thou King Pedro's glove? |

118 |

ONIS.

| Now heaven defend!— |

119 |

| That voice! — |

120 |

HENRY.

[Stepping forward.]

DU GUESCLIN.

[rising, and laying his own hand on Henry's arm.]

| Forbear, rash king! |

122 |

| Herald! go back in safety as thou camest, |

123 |

| And tell thy master that the King Don Henry |

124 |

| Would willingly have lifted up the glove |

125 |

| Thy had flung down — but that Du Guesclin stayed him. |

126 |

HENRY.

| French Lord, I do command thee, let me pass. |

127 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| Nay, nay King Henry — thou art not my king. |

128 |

HENRY.

| Thou art the vassal of my brother of France, |

129 |

| [Page 49] |

|

| And thou art here because my quarrel's his. |

130 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| Yes; but his quarrel is not thine, Lord King —— |

131 |

| Nor, when he kissed my baton at the Louvre |

132 |

| Did he command me to entrust the vengeance, |

133 |

| For which dead Blanche's blood doth cry to heaven |

134 |

| And him, the royal brother of her blood, |

135 |

| To any Spanish hand — prince's or king's. |

136 |

| We, De la Houssaye, and Le Begue, and I, |

137 |

| And ten good score of noblemen besides, |

138 |

| With all the spears that love or chivalry |

139 |

| Has clustered at our backs — must we stand by |

140 |

| And let the murderer of the Lady Blanche, |

141 |

| The sister of our king, conquer or fall, |

142 |

| According as one Spaniard or another |

143 |

| Couches his lance the firmest, in our sight — |

144 |

| Had Henry of Transtamara ne'er been crowned — |

145 |

| Aye, had ne'er been born, thinkest thou my king |

146 |

| Would have sat still upon his father's throne, |

147 |

| And bid his priests sing masses for the soul |

148 |

| Of unrevenged Blanche. |

149 |

| I lift this glove; |

150 |

| I place it in the front of this my basnet, |

151 |

| Which here, for lack of worthier, represents |

152 |

| The coronetted helmet of King Philip. |

153 |

| Do as ye will, thou, and the Lord of Onis, |

154 |

| This bishop, and as many Spaniards more |

155 |

| As are encamped with us — I speak for France, |

156 |

| [Page 50] |

|

| And I will have a field, an open field, |

157 |

| A bloody field for Blanche! |

158 |

HERALD.

| A bloody field! |

159 |

| So be it—I shall know my glove again. |

160 |

DU GUESCLIN.

HERALD.

| King Pedro's glove. I speak for him. |

162 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| Thou speakest in safety whatsoe'er thou speakest. |

163 |

HERALD.

[taking off his cap.]

| I speak in safety since Du Guesclin says so, |

164 |

| I am King Pedro! Doth Henry know me? Kneel slave! |

165 |

HENRY.

[starting back, and drawing his sword.]

| Thou murderer! hast no sword? |

166 |

DU GUESCLIN.

| If he had fifty none were drawn to-night. |

167 |

| This sacred garb which God and man respect, |

168 |

| And mine own words do save thee. Go in peace. |

169 |

PEDRO.

| I came not hither to make speeches, nor |

170 |

| See I fit judge to sit and hold the balance |

171 |

| Between my breath and thine. Therefore, Du Guesclin, |

172 |

| Farewell. We meet to-morrow. Ynigo Onis |

173 |